The September 1926 edition of Architecture magazine featured an article titled “Mariemont, An Adventure in Humanitarianism”. The article described the village that John Nolen had planned in cooperation with Mary Emery and Charles Livingood as “…this practical contribution to humanity’s highest aim, a better place to live.”

The sales brochure prepared by The Mariemont Company (the Company) in 1925 describes Mariemont as the most comprehensive real estate development of its kind. There are plans for shops, markets, a theater, a hotel, banks, a post office, a library, a museum, and a town hall within easy walking distance of every resident. But it goes on to explain that Mariemont is not being developed as a philanthropy nor is it to be paternalistic in any sense. It is an ordinary real estate development on normal American lines. It is simply intended primarily for a wide range of families of different economic situations who prefer not to live “under the shadow of the factory” just as long as they are not too far from their work. It is hoped that it wouldn’t be for any special class of workers nor for workers solely.

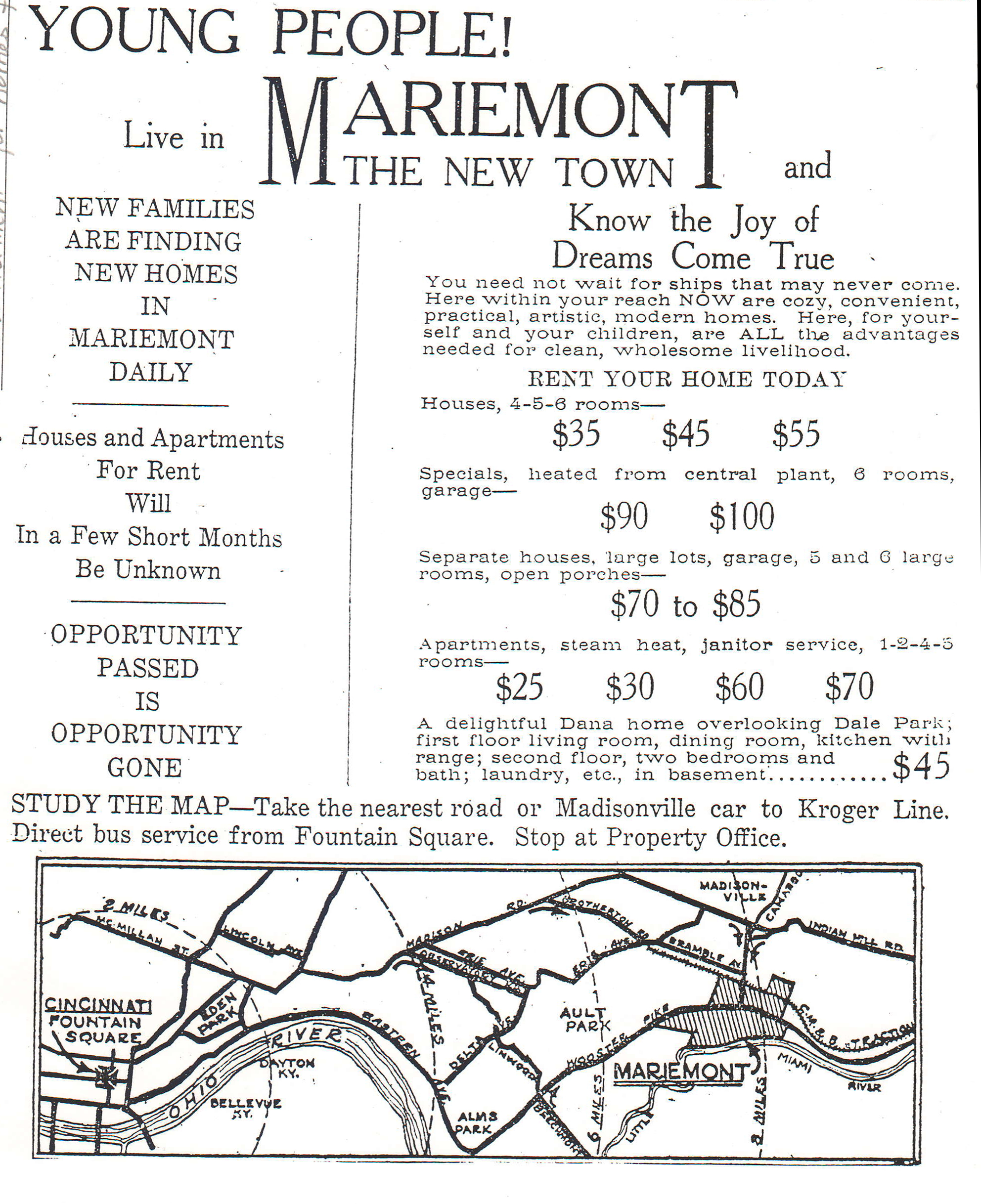

To accomplish these ambitious plans as quickly as possible the first homes were for rental only. An advertisement in the Cincinnati papers read:

MOVE TO MARIEMONT

Children Welcome – Mariemont Needs Them

Touch-the-Button Apartments

Built-In Beds

Built-In Iceboxes

Built-In Kitchen Cabinets

Electric Lights

Running Hot Water

On April 24,1924 the Company began building “homes for the people” (apartments and group houses) in the new Dale Park District. While the “projectors” of Mariemont (i.e. Mary Emery) “…stood four-square for home ownership, that was not within the reach of everybody at once, so the first homes were being rented as cheaply as possible”. The average rentals for these well built apartments were in the neighborhood of $50 – $60 per month but were still almost half again that of an equivalent four room apartment in the city.

The MacKenzie apartments and group houses at the corner of Murray Avenue and Beech Street formed a gateway into the Dale Park section.The apartments in the large building were planned to meet the needs of a small family that only needed a compact space but wanted all of the modern conveniences. It was planned that this family might be able later to move to one of the group houses on either side of the building for larger accommodations and a garden so that the family wouldn’t need to move away from the neighborhood and friends.

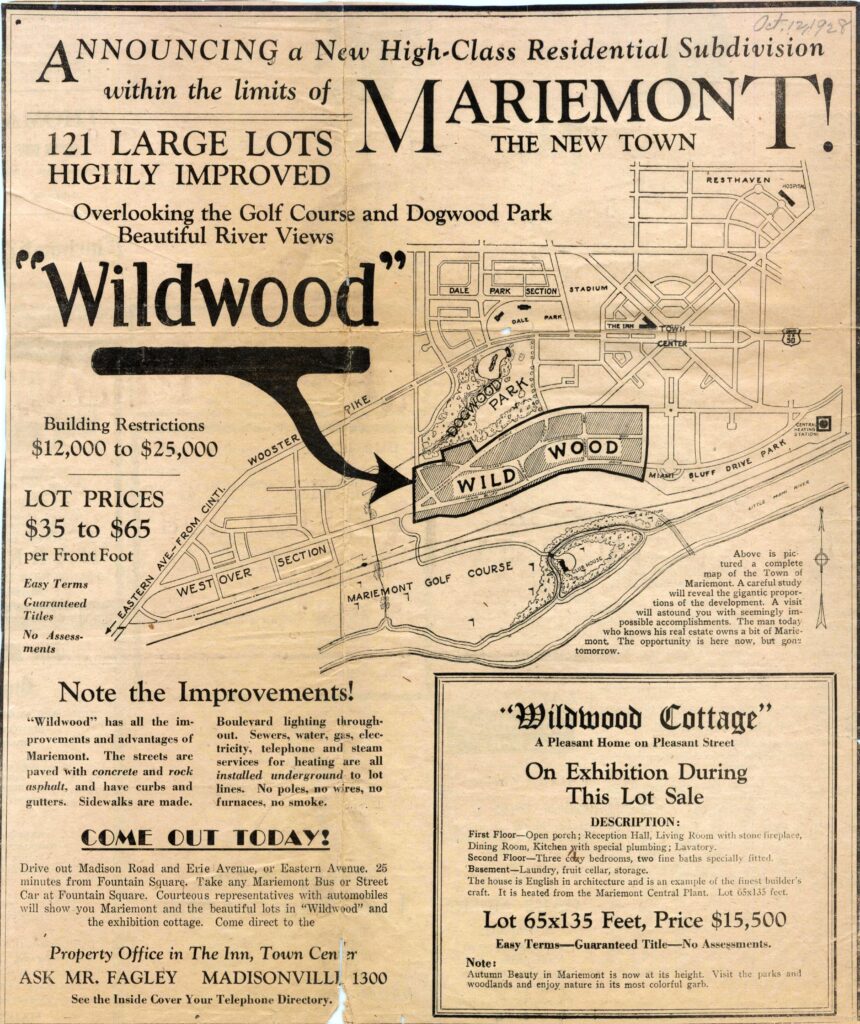

Besides the group housing in the Dale Park section about sixty lots were left for those who wanted to build for themselves in this section. John Nolen’s plan screened the working class row houses in Dale Park with a buffer of two blocks of single family lots along Wooster Pike. By January of 1926 there were 211 families living in Mariemont versus only the 77 families that had been living there in May 1925.

John Nolen also understood the desirability of an automobile for life in Mariemont because it was still considered to be “too far out of town”. The original design for Maple Street was planned so that for the safety of the children at play there would be no thoroughfare street. As a result there were to be no curbs or driveways but that plan had to be changed so that the residents could park their cars close to their homes. He also understood the necessity of making a good first impression on visitors (and prospective buyers) driving to Mariemont from the city along Wooster Pike. The “pretty frame cottages with rose covered porches” of Linden Place would be the first to greet people who were arriving from the west, and was intended to be a typical residence for people of moderate means.

Some early advertising (1926) mentioned that when you own a home in Mariemont the deed restrictions would protect your investment. Most of these restrictions in the land contracts and deeds concerned such things as walls and fences, signs, set backs from the street, the widths of side yards, and prohibitions of livestock.

But one restriction (number 8) concerned occupants: “No lot shall be sold, conveyed, rented, leased or mortgaged to or occupied, except as a house servant, by a person of African or Asiatic descent.” In his book “John Nolen & Mariemont” Millard F. Rogers, Jr. points out (page 177), “Such prohibitions were common in Cincinnati and other cities in the 1920’s, where segregated schools, housing and entertainment centers prevailed. It is ironic that these prohibitions by the Mariemont Company were instituted, for their tenor was contrary to Thomas J. Emery’s compassionate interest and long record, as well as Mary Emery’s, in support of African-American causes, whether segregated (as with orphanages) or when demanding equal admittance for black as well as white students to the Ohio Mechanics Institute.” In his book “Rich in Good Works” Millard F. Rogers, Jr. relates (page 52) that by 1903 Thomas had begun a friendship with Booker T. Washington and welcomed him to his house for dinner. Thomas told a reporter he “considered what transpired at dinner a private matter and would not divulge the object of Mr. Washington’s visit further than to say that it was in the interest of Tuskegee Institute” of which Mr. Washington was then president.

In Charles Livingood’s letter of January 14, 1928 to John Nolen he proudly points out that the hospital is nearing completion and will soon add another reason for living in Mariemont. He also says that the the one thing that attracts the most attention is the Memorial Church with its marvelous roof brought over from England. Although Mary Emery was a staunch Episcopalian, she had instructed that a chapel was to be built in memory of the earliest settlers to be used primarily for weddings and funerals but not to be operated by any one denomination. In fact, the sales brochures refer to the fact that lots were being set aside for churches that the residents could build themselves for the denomination of their choosing, although none were built.

In that same letter from 1928 Livingood says that their greatest trouble has been with architects and builders. Architects don’t seem to know or care anything about the costs of the houses they design, and prospective buyers are reluctant to deal with a builder who cannot guarantee them the costs they are committing to undertake. By that time about fifty houses had been built by individuals but in most cases the Company had to lend them money through the building association. The high quality of the materials being used and the architectural restrictions imposed in Mariemont seemed to be driving people to neighborhoods where there was no regard for quality or taste according to Livingood. However, everything in Dale Park was rented at that time.

By 1930 the country was in the early days of the Great Depression, and sales activity had slowed down. In the minutes of the January 20, 1931 meeting of the stockholders of the Company to review the full year 1930 it was noted that two houses had been sold during the year. The first at 6920 Miami Bluff for $29,500, and the other at 6508 Mariemont Avenue for $22,500. Both of these were considered satisfactory prices for their higher class properties under the economic circumstances. It was also noted that they considered it significant that none of their builders had gone bankrupt during 1930, although three or four had required help from the building association. Finally, on a more optimistic note it was noted that the total number of resident families as of December 31,1930 was 392 and had held steady versus 391 for the same date in 1929.

But by November 9, 1932 activity had worsened. Warren W. Parks reported in a letter to John Nolen that there were now just 290 families living in Mariemont. The vacancy rate was now about 40%, and rentals which included heat and janitor service ranged from $12.50 for one room and a bath to $45 for five rooms and a bath. The prices to buy houses ran from $7,500 to $25,000. Houses that could be rented ranged from $28.50 for three rooms, bath and garage to $70.00 for six rooms bath and garage.

Just as in the rest of the country it was going to be awhile until the economic situation improved enough in Mariemont for sale and rentals to pick back up. However, what the report of the Better Housing League of Cincinnati had stated in their report dated December 1925 was still true:

“Mariemont has made an important contribution to housing in this community. Laid out long the best city planning lines, developed with the greatest care and directed by the best engineering ability, there is no similar home building project in the country anything like so comprehensive as Mariemont. There has been much misunderstanding as to what Mariemont was expected to do and disappointment in the minds of many because it has not done what those unfamiliar with its aims had hoped for. Mariemont was not projected for the purpose of meeting the housing shortage, nor primarily to furnish homes for the lowest economic groups. It was intended rather to be a demonstration of good housing and city planning, providing homes for people of all economic grades from those in moderate circumstances on up the scale.

Begun in a period of high costs, their rents are higher than the Company expected. Nevertheless, Mariemont has added to the housing accomodations in Cincinnati, providing homes for nearly 300 families in addition to what would have been provided through the usual channels. It will, we believe, influence home building and planning of residence areas in Cincinnati for years to come. Here we have at least one self-contained community which should forever remain free of slums. Its value is far more appreciated elsewhere than in Cincinnati.”

For further reading view ” Descriptive & Pictured Story of Mariemont – A New Town“

To purchase Millard F. Rogers book on John Nolen:

Last modified: January 23, 2024